In this brief analysis, we examine how a sequence of unusual climatic conditions combined to make 2025 a record-breaking wildfire year in the United Kingdom, using methods consistent with those applied in the State of the Wildfire Report.

Wildfires and the UK are not often associated. Cool temperatures, frequent rainfall and fragmented landscapes have historically limited the kind of large, fast-moving fires seen in vast boreal forests or savannas. But the wildfire season of 2025 challenged that perception, highlighting an emerging danger driven by increasingly extreme weather patterns.

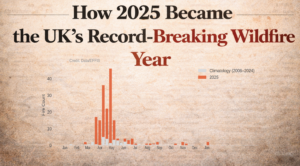

The foundations for this season were set months earlier. During the winter of 2024/2025, much of the UK experienced below-average precipitation, initiating early landscape drying. An exception occurred in northeast Scotland, where wetter-than-average conditions promoted spring growth, ultimately creating abundant fuel for later in the year. The spring that followed was the warmest and sunniest on record, around 1.4 °C warmer than the long-term UK average, while the UK received just 56% of average precipitation. These conditions, summarised in Figure 1, created an extended period of fuel drying just as grasses, heather, and other surface vegetation emerged. Instead of entering summer with moisture-replenished soils and resilient live fuels, large parts of the landscape were already primed for fire activity.

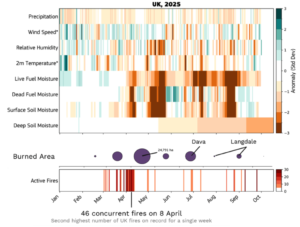

Figure 1. Daily 2025 standardized anomalies of key variables influencing wildfire risk, derived from ERA5-Land data and the Sparky-Fuel model, relative to 2003–2024 climatology for the UK (top). * indicates reversed anomalies. Monthly UK burned area is shown from MODIS Collection 6.1 (purple bubbles), and daily active fires for the UK are also from MODIS C6.1.

Spring wildfires in the UK are not uncommon; most fires in a typical year occur during these months, fuelled by the drying of fine, dead vegetation from the previous season. However, 2025 saw the season start unusually early, with over 30,000 hectares burned by early May. On 8 April, satellite monitoring recorded 46 concurrent fires, the second-highest single-week total since 2006, highlighting the unusually widespread nature of early-season ignitions. Across the spring, 170 fires were recorded, far above the long-term average of 36, although the average fire size remained typical, indicating that the early-season activity was driven by many small to medium events.

Warm anomalies persisted, producing the warmest summer on record in the UK. Overall rainfall was only slightly below average, but much of it fell in short, intense bursts, separated by prolonged dry spells, driving a notable shift in fire behaviour. As shown in Figure 2, the relationship between the number of active fires and the total area burned diverged. Spring featured many fires burning modest areas, while summer saw an average number of fires but more severe and longer-lasting events, fuelled by sustained heatwaves and prolonged fuel dryness. The impact was particularly evident in live fuel moisture, which remained critically low throughout summer. Additionally, deep soils were moisture-depleted, allowing fires to penetrate and persist in peat layers, contributing to prolonged burning.

Figure 2. Weekly active fire count (top), burned area (middle), and average fire size (bottom) across the UK in 2025 compared with the 2006–2024 mean. Data were obtained from the European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS).

Of these few high-impact summer fires, two stand out. The Dava and Carrbridge fires in the Scottish Highlands burned 11,827 hectares, marking the UK’s first recorded “megafire.” Unlike short-lived spring fires, these incidents persisted for several days (28–30 June), only being suppressed after heavy rainfall. The unusually wet winter of 2024/25 likely enhanced spring vegetation, increasing fuel continuity and enabling such a large area to burn.

The second notable event was the Langdale Moor wildfire in North Yorkshire, igniting on 11 August. Smaller than Dava and Carrbridge, it burned for over six weeks until 23 September, with potential deep soil smouldering into winter. Comparable to the Saddleworth Moor fire of 2018, it had small flame fronts but proved challenging to extinguish due to deep peat burning. Its longevity was driven by prolonged moisture deficits in near-surface and deep soils, particularly pronounced from mid-August onward.

Alongside these events, 2025 also showcased advances in fire forecasting. Figure 3 highlights the experimental Sparky–Probability of Fire product from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). Using machine learning, it integrates weather, fuel characteristics, and socioeconomic factors, producing forecasts with far finer spatial granularity than traditional fire-weather indices and provides a forecast of likely wildfire locations.

Figure 3. Map of Scotland showing the location of the Dava and Carrbridge fires (left). Forecast conditions for 28 June 2025 are illustrated using the Fire Weather Index (FWI; top right) and the Sparky–Probability of Fire model (bottom right).

While the 2025 season was anomalous, it may offer a preview of future wildfire behaviour in the UK. Even modest temperature increases, combined with rainfall deficits, can dramatically alter fuel conditions, producing not only more frequent early-season fires, but also fires that behave differently, arriving earlier, lasting longer, and occasionally reaching scales previously unseen.

References

European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS), 2025. Dataset: Wildfire burned area and active fire data. Copernicus Emergency Management Service, European Commission. Available at: https://forest-fire.emergency.copernicus.eu/ (Accessed: [15/02/2026]).

Giglio, L., Boschetti, L., Roy, D.P., Humber, M.L. and Justice, C.O., 2018. *MCD64A1 MODIS Burned Area Monthly L3 Global 500m SIN Grid V061*. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC. Available at: https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mcd64a1v061/ (Accessed: [20/12/2026]).

Giglio, L., Schroeder, W. and Justice, C.O., 2016. *MODIS Active Fire Detections (MOD14/MYD14) Collection 6*. NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC. Available at: https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod14v006/ (Accessed: [20/12/2026]).

McNorton, J., Di Giuseppe, F., Pinnington, E., Chantry, M. & Barnard, C., 2024. *A Global Probability‑of‑Fire (PoF) Forecast*. Geophysical Research Letters, 51(12), e2023GL107929. doi:10.1029/2023GL107929.